The Rohingya crisis:: Living in Limbo

- Get link

- Other Apps

Months after coverage of their displacement has died down, thousands of refugees still face difficult conditions

Mila Akhter, who arrived six months ago at the Balukhali camp with her infant, who is now 10-months old.

The mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of oppressed Rohingya from Myanmar last year made international headlines as the world’s fastest growing refugee crisis. Six months later, the plight of the ethnic minority has largely fallen off the front pages, despite the fact that there is no end in sight for the nearly 690,000 people displaced by the crisis.

For decades, Rohingya have faced discrimination and persecution in Buddhist-majority Myanmar. They began fleeing in August 2017, after Rohingya insurgents attacked police posts and an army base, and Myanmar's military responded with a violent crackdown. The Rohingya were forced to escape to neighbouring Bangladesh, and an eventual return to Myanmar is a distant hope for them.

Canadian photojournalist Renaud Philippe recently travelled to Bangladesh to document life in the Rohingya refugee camps. Amidst the hilly, sprawling and crowded camps, Mr. Philippe saw endless evidence of trauma against the long-oppressed minority. But he also witnessed the Rohingya experiencing new-found freedoms: the opportunity to play sports, listen to music, and practise their religion. These are their stories.

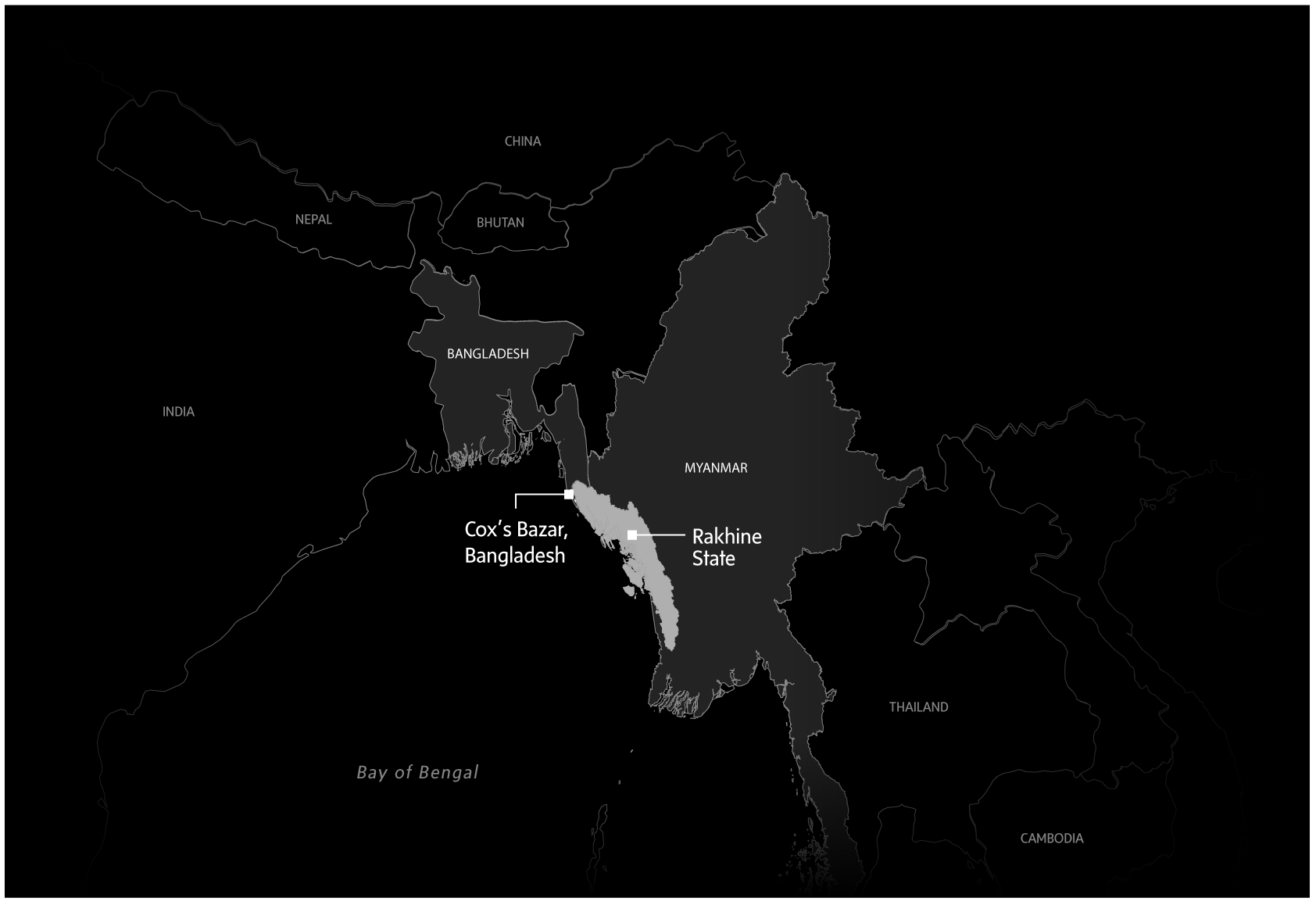

Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh

More than 688,000 refugees have arrived in Cox’s Bazar since August 2017 ...

...of which 547,000 have settled in the giant Kutupalong and Balukhali camps alone.

Bamboo stilts and plastic tarps have been used to construct makeshift housing and infrastructure in the camps. Hastily built bamboo bridges allow people to move around the hilly area.

A store sells basic staples, fruit, biscuits and cigarettes next to a flooded area. Water is slowly creeping into parts of the camps, soaking areas that were once inhabited by Rohingya refugees.

Small refugee-run markets, like this one in Balukhali, have emerged across the camps. Rohingya use whatever money they get from odd jobs and donations to buy items.

Zorina Khatun, 53

Peraieng Daong village in Myanmar

I had a big house, lots of cows, a farm. We were a wealthy family, now I have nothing left.

A young Buddhist in a military uniform arrived in Ms. Khatun’s village, where there were 360 families. All of them were arrested. Their hands were tied behind their backs, and the younger villagers were beaten up. Her 25-year-old brother and two of her nephews were shot dead in front of her. “He did not do anything to deserve that. Just because he was Rohingya.” The soldiers burned many people alive, including women and children. She said they burned their houses and belongings, setting everything on fire.

Green algae fill a pond, which is situated near latrines leaking human waste. NGOs fear the coming cyclone season – from March through July – could wash away parts of the camps.

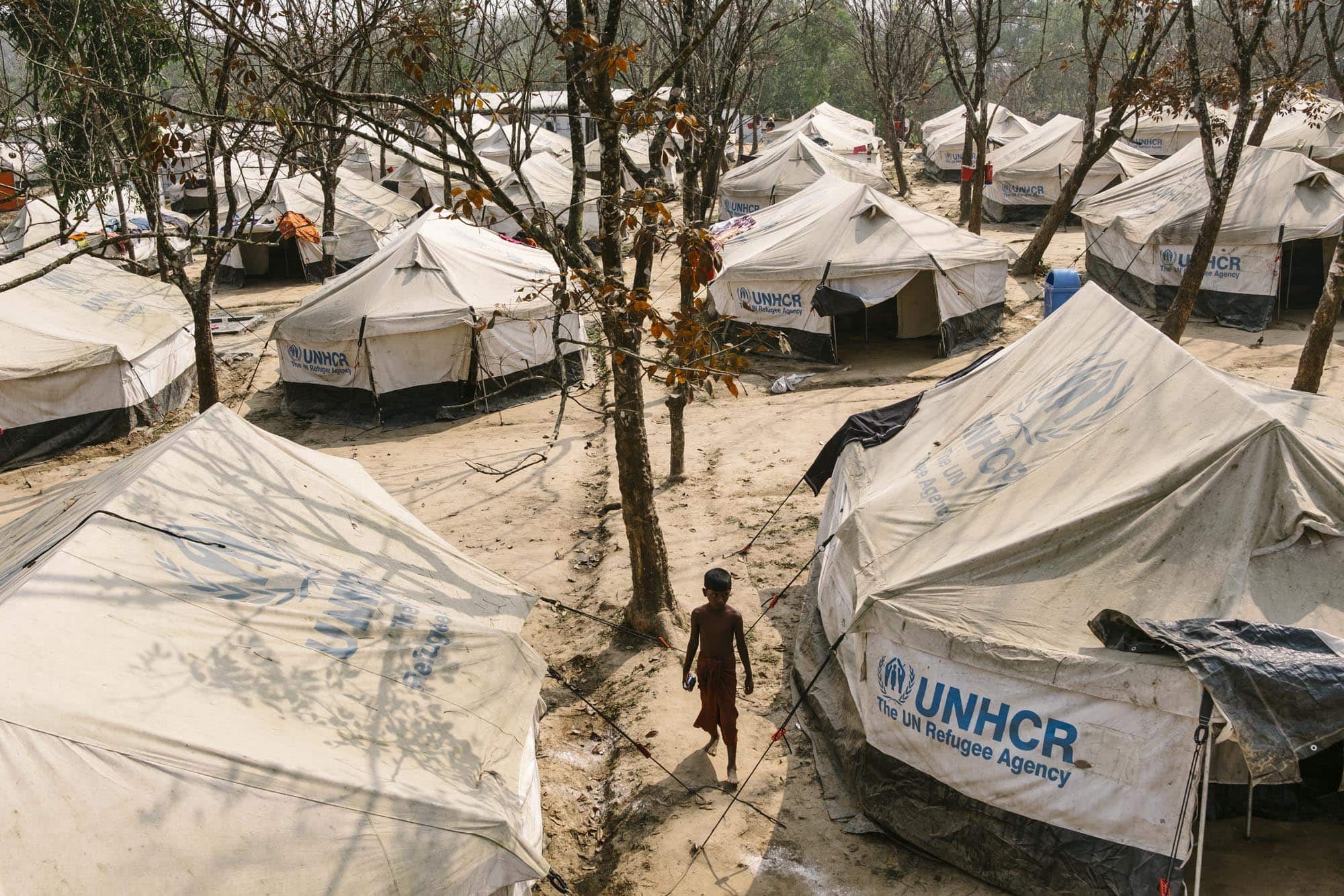

Newcomers spend up to a week at the UNHCR transit centre in Kutupalong before being assigned a hut in the camp.

Yasmine Ara, 4, receives treatment for diphtheria at a centre run by Doctors Without Borders. The sanitary conditions of the camps and potential for further disease outbreaks are worrisome as the cyclone season approaches.

In the evening, some families eat under electrical lighting powered by solar panels donated by a local NGO.

Rajuma Begum, 20

Arrived in the camp Aug. 6, 2017

Seven of Ms. Begum’s family members were killed in front of her eyes, including her two younger sisters and little brother. Her one-year-old baby was also burned alive.

Ten soldiers came towards the villagers and ordered 25 young women, including Ms. Begum, to come with them. The soldiers would do “what they wanted with the girls.” She was raped, beaten and left for dead.

After the attack, Ms. Begum fled to Bangladesh. On the way she met another woman with her child, who joined her for the journey. At the border, they saw many other Rohingya waiting to cross and realized that what happened in their village wasn’t an isolated incident. Everyone has similar stories.

After the attack, Ms. Begum fled to Bangladesh. On the way she met another woman with her child, who joined her for the journey. At the border, they saw many other Rohingya waiting to cross and realized that what happened in their village wasn’t an isolated incident. Everyone has similar stories.

Refugees have used bamboo to construct stairs on the hilly terrain, and plastic tarps to build other parts of the camp.

When people wait for their monthly food rations, lines often weave around the camps.

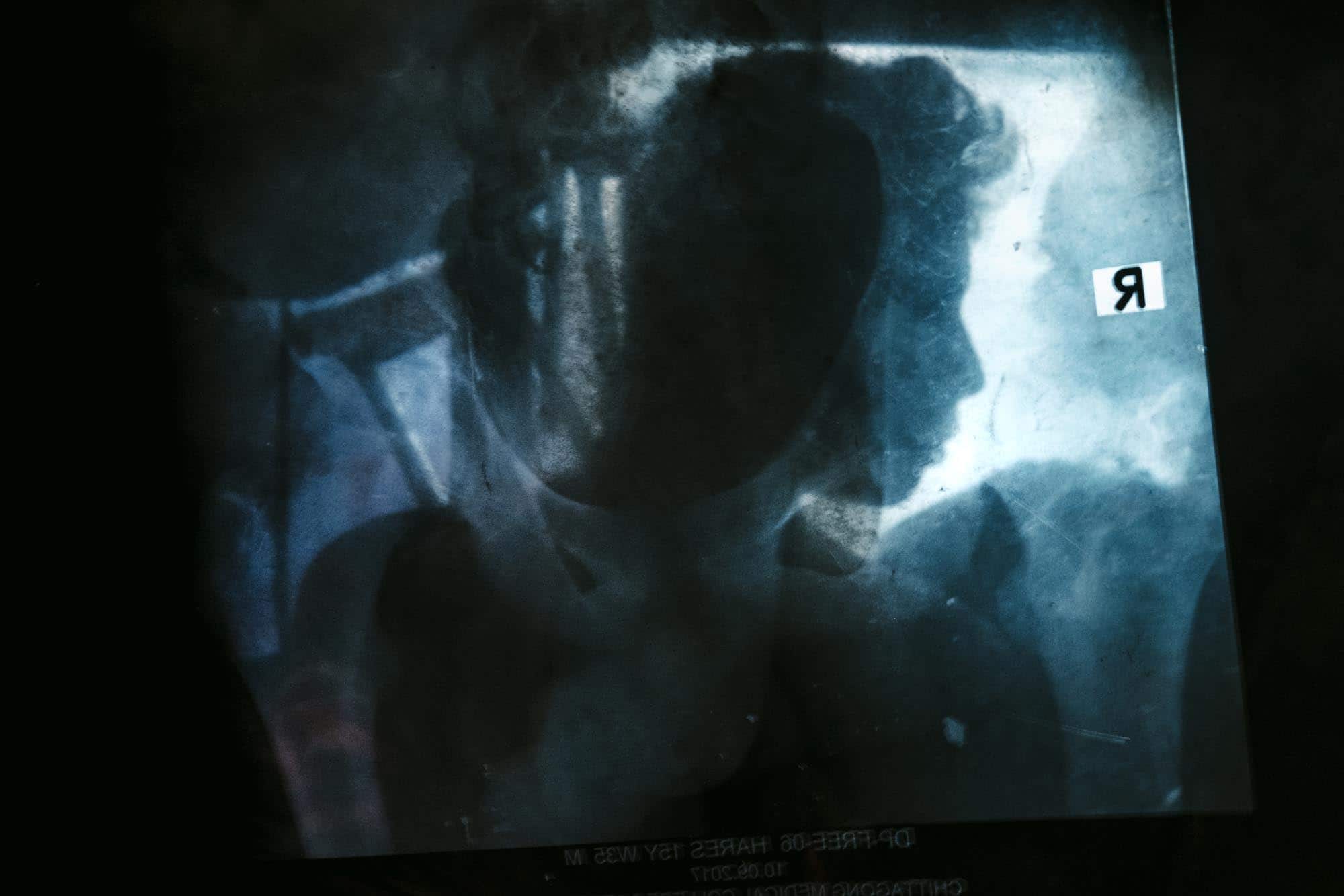

Mohammad Haras, 12

Lived in the village of Tong Bazar

Mohammad recounted how, one day, soldiers ordered them to stay in their homes all day and night. A few days later, on Aug. 26, 2017, the soldiers returned and started firing at people. A bullet struck his pelvis, and he passed out. His brother-in-law carried him to the forest, where he remained unconscious. They hid for 12 days.

The Bangladeshi military and border security forces found them and called a Doctors Without Borders ambulance. Mohammad was brought to the hospital in Kutupalong. He was then transferred to another hospital in Chittagong, Bangladesh, where he was treated for a month.

Mohammad can no longer walk or control his bladder. He had no memory of what happened from when he was shot until he got to the border and was treated by Bangladeshi doctors. He only regained full consciousness after 10 days at Chittagong Hospital.

The Bangladeshi military and border security forces found them and called a Doctors Without Borders ambulance. Mohammad was brought to the hospital in Kutupalong. He was then transferred to another hospital in Chittagong, Bangladesh, where he was treated for a month.

Mohammad can no longer walk or control his bladder. He had no memory of what happened from when he was shot until he got to the border and was treated by Bangladeshi doctors. He only regained full consciousness after 10 days at Chittagong Hospital.

Rohingya who crossed the border since August joined more than 300,000 who were already refugees in Bangladesh from previous waves of violence against the minority group in Myanmar. Some of the Rohingya who fled to Bangladesh now work as fisherman in Shamlapur, near the coast.

A group of boys have set up a makeshift net at one of the camps. Even playing sports was out of reach for many in Myanmar since the Rohingya were unable to gather.

A refugee hairdresser sets up shop in the Kutupalong camp.

The Rohingya fishermen in Shamlapur work seven days a week, making a pittance going out to sea at night.

During the day, they do maintenance on the boats.

Alima Khatoon, 35

Farmer in Myanmar

Ms. Khatoon arrived in the camp on Aug. 6, 2017, having seen her whole family – parents, siblings, cousins, uncles and aunts – killed before her eyes in Myanmar.

Everyone fled when soldiers entered her village of 3,000 Rohingya residents. Survivors from her family hid in the forest without food for 11 days. The soldiers came back to round them up and fired into the crowd. Her 20 relatives died as they tried to run away. She managed to flee with her husband, two daughters and son.

Ms. Khatoon said her life is much better in the Bangladeshi refugee camp. She feels free in the camp, compared to life in Myanmar, where Rohingya are constantly under threat from the military.

Everyone fled when soldiers entered her village of 3,000 Rohingya residents. Survivors from her family hid in the forest without food for 11 days. The soldiers came back to round them up and fired into the crowd. Her 20 relatives died as they tried to run away. She managed to flee with her husband, two daughters and son.

Ms. Khatoon said her life is much better in the Bangladeshi refugee camp. She feels free in the camp, compared to life in Myanmar, where Rohingya are constantly under threat from the military.

Many Rohingya women wear headscarves in the camps. Mr. Philippe said refugees told him they were not allowed to wear their headscarves in public back home.

Widespread cultural oppression prohibited Rohingya from attending parties – like the wedding pictured at a camp here – and playing music in Myanmar.

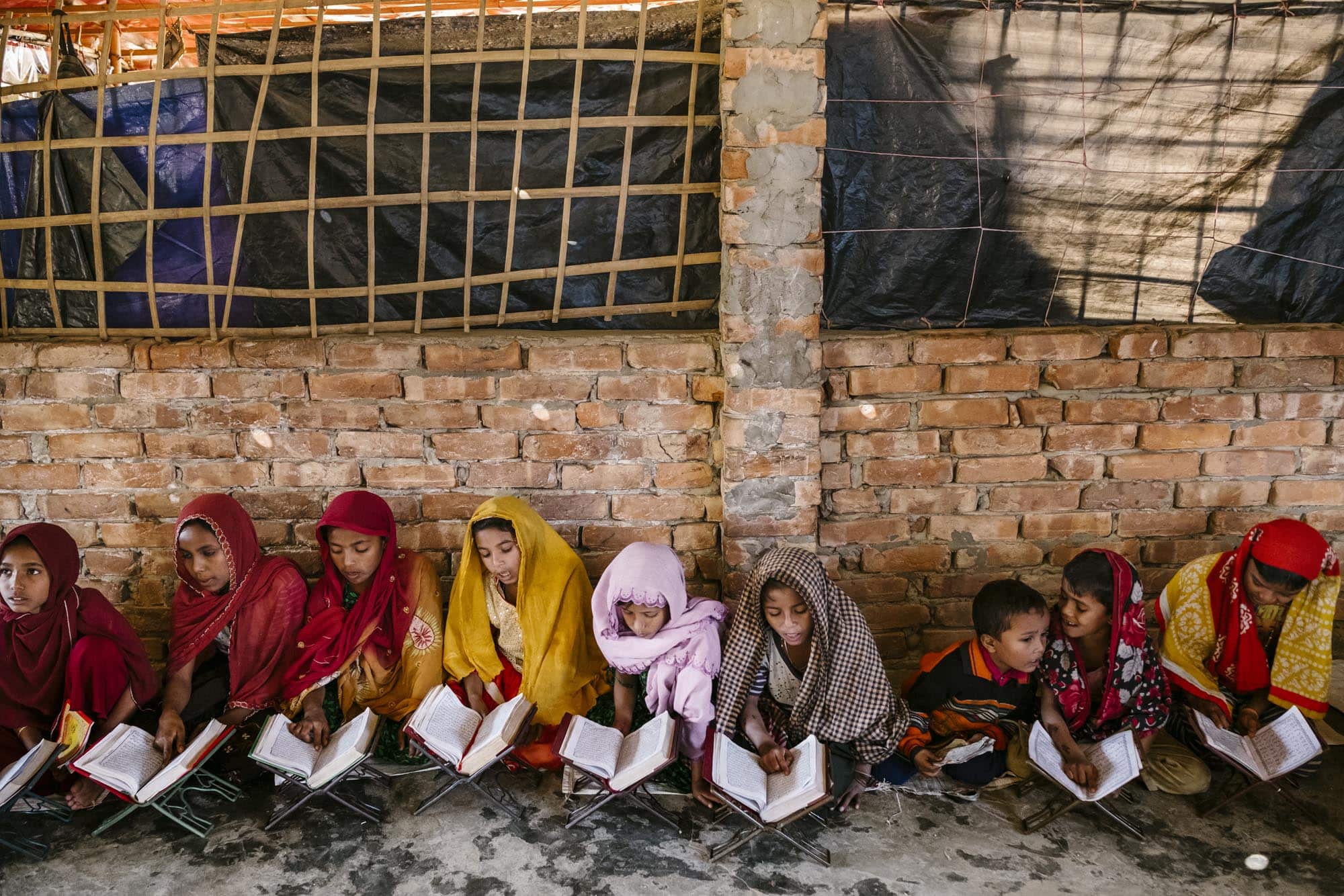

Children are able to read the Koran at improvised madrasas (or religious schools) in the camp.

A blind man prays in his hut. Refugees living with disabilities spend most of their time inside because they are not able to safely move around the poorly built camps.

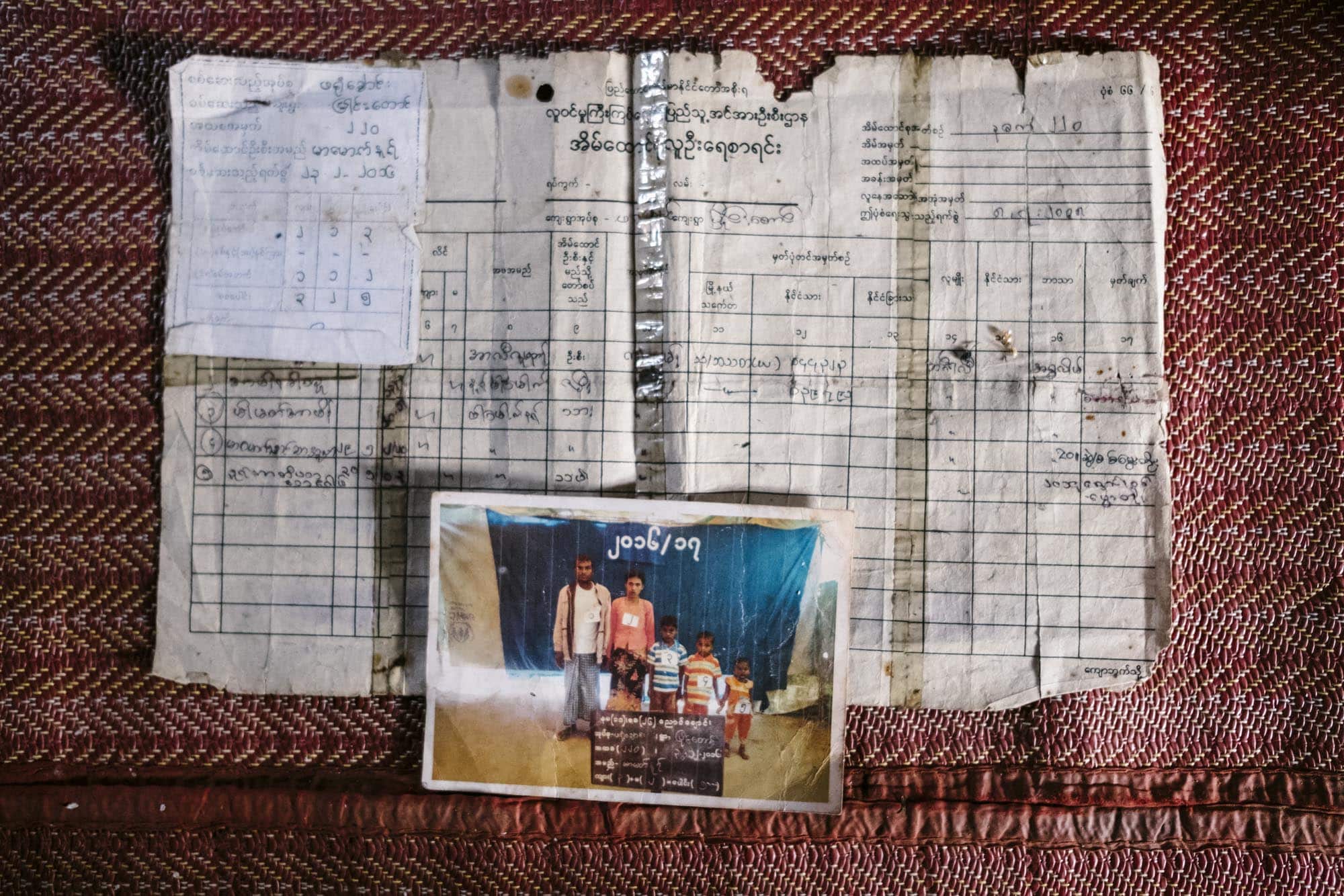

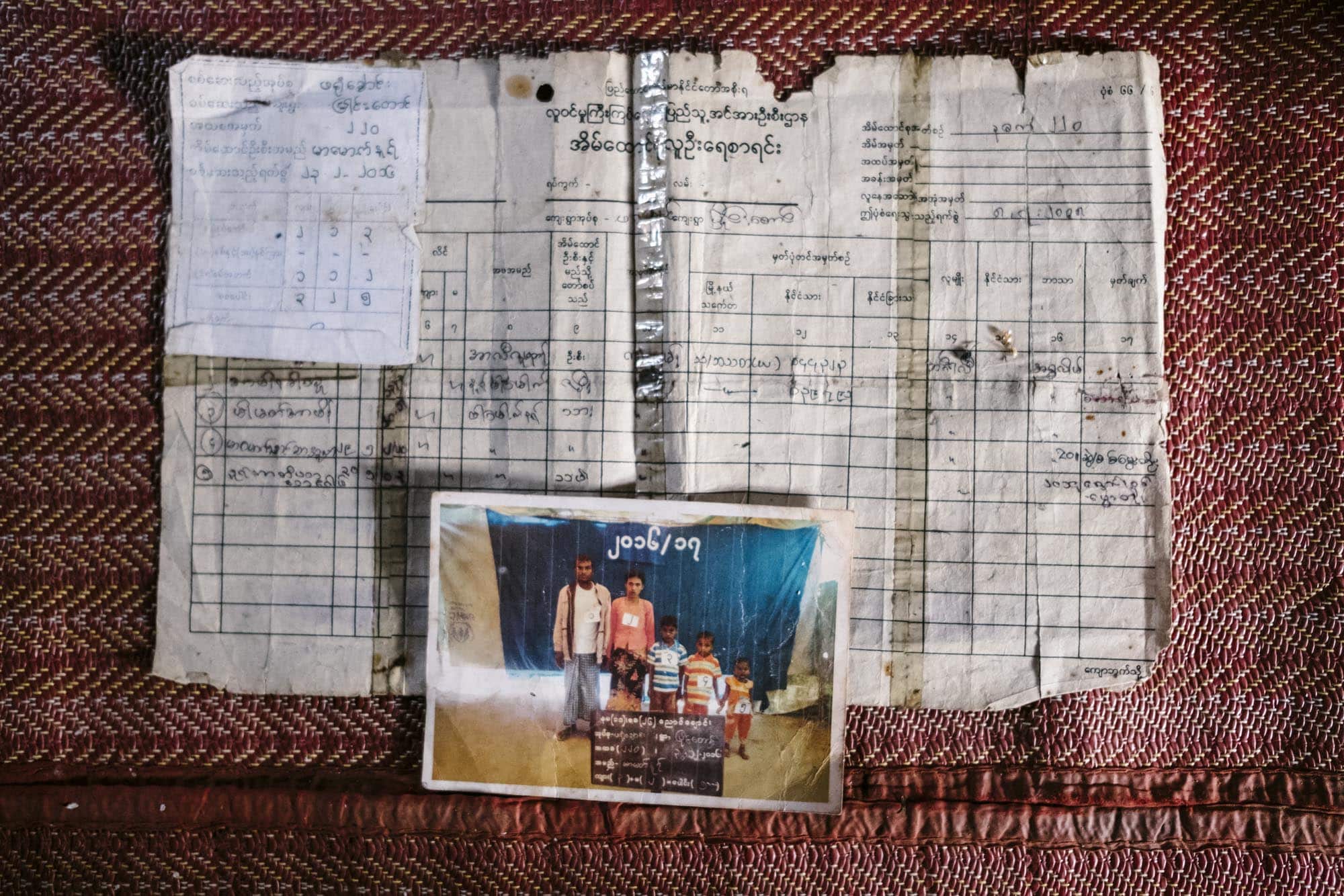

Nearly every Rohingya crossed into Bangladesh with these border documents. They have no other form of documentation from Myanmar.

Every year in Myanmar, the border security force, known as Nasaka, takes pictures of all Rohingya. The Nasaka control every aspect of life.

Mohammad Sobhi, 60

Eight months ago, Mr. Sobhi was shot while cutting rice in the fields.

Even though I'm alive, I'm dead. I'm nothing in the world anymore. I was very strong before it happened. Why do they want to destroy us?

Mr. Sobhi said the military approached while he was in the field. Others around him started to run away, but he didn’t see the soldiers. “They did not say anything, they just shot me from behind.”

Mr. Sobhi remained on the ground, left for dead with bullets in his leg. After the soldiers left, the others came back and took him to be treated by Rohingya medics, as it was too dangerous to go to a government hospital.

For two weeks, Mr. Sobhi received care from fellow Rohingya but did not see any improvement in his health. The pain remained and his whole leg became infected. His family paid two men to carry him across the border to Bangladesh. He spent two months in a Chittagong hospital, where his leg was amputated. After his operation, he returned to his village in Myanmar and stayed there for two months. When the soldiers returned again, he fled to Bangladesh.

Mr. Sobhi remained on the ground, left for dead with bullets in his leg. After the soldiers left, the others came back and took him to be treated by Rohingya medics, as it was too dangerous to go to a government hospital.

For two weeks, Mr. Sobhi received care from fellow Rohingya but did not see any improvement in his health. The pain remained and his whole leg became infected. His family paid two men to carry him across the border to Bangladesh. He spent two months in a Chittagong hospital, where his leg was amputated. After his operation, he returned to his village in Myanmar and stayed there for two months. When the soldiers returned again, he fled to Bangladesh.

Renaud Philippe is a photographer based in Montréal.

Comments

Post a Comment